Asbestos has been mined and used for more than 1,000 years for its excellent heat-resistent properties, although, due to health concerns, many countries have now banned or restricted its use in products. Commercially processed, asbestos-containing materials, such as insulation, fire retardants, and automobile brake linings, are known to be a health hazard if damaged and released into the air. Asbestos also occurs naturally in rock and soil. Disturbing these fibrous minerals through geological processes such as weathering and erosion or human activity can release tiny asbestos fibers, as dust too small to see, into the air, creating an environmental health concern.

Winchite-richterite asbestos image from scanning electron microscope. Photo credit: U.S. Geological Survey.

Exposure to airborne asbestos increases your risk of developing lung diseases such as asbestosis (scarring of the lung), lung cancer, and malignant mesothelioma and other cancers. Once you breathe in the needle-like abestos fibers, which are resistant to heat, chemical, and biological breakdown, they could stay in your lungs for a lifetime. Being exposed to asbestos, however, does not always mean you will develop health problems. Important risk factors include length, frequency, and amount of exposure; time since beginning of exposure; what size and type of asbestos you were exposed to; and whether or not you smoke cigarettes or have other lung conditions.

Six naturally occurring asbestos (NOA) minerals (chrysotile, amosite, crocidolite, fibrous tremolite, fibrous anthophyllite, and fibrous actinolite) are regulated through testing and the use of construction materials in Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities (DOT&PF) statutes. Other unregulated asbestiform minerals are known to occur in Alaska and may have similar health concerns as the regulated asbestos minerals (data table of known asbestos occurrences).

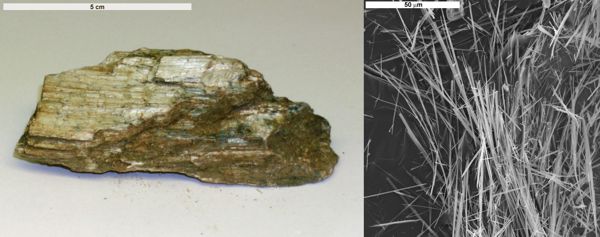

Asbestiform tremolite, seen in hand sample (left) and scanning electron micrograph (right). Photo credit: U.S. Geological Survey.

Naturally occurring asbestiform minerals develop in predictable geologic settings worldwide. DGGS has identified rock units in Alaska associated with these settings and created a series of maps showing the rock units' potential to contain asbestos. Sediments and gravels, which were not evaluated in this study, may also contain asbestos, particularly near bedrock areas determined to have a higher potential for asbestiform minerals.

Exposure to airborne asbestos from construction projects, travel on unpaved roads, and living in areas with natural asbestos deposits can be reduced by leaving soil and rock in place and undisturbed, covering or capping asbestos-bearing material, and limiting or managing dust-generating activities, such as using entryway doormats to reduce tracked-in soil and wetting your garden before planting. More ideas are available from the CDC and EPA.